As we toured the battlefield national park area as well as walked around the old part of town, we began to get a feel for what transpired here almost 150 years ago. It was both sobering and inspiring.

ORDINARY HOMES

General Burnside (Union) wanted to capture Richmond (thus ending the war, in his opinion) which required crossing the Rappahannock River into Fredericksburg. But it would not be an easy endeavor as General Lee (Confederate) had taken the precaution some time ago of burning all the bridges across the wide river. Burnside's plan was to meet the Army engineers across the river from Fredericksburg, have them build a pontoon bridge and then, with the element of surprise on their side, march into town. However, the pontoons arrived ten days late, the element of surprise was lost and the Confederate Army was ready and waiting.

General Burnside made his headquarters at Chatham Manor (the Lacy House) on the east side of the river, which had been used by the Union Army since April, 1862. The plantation owner (and slave owner), James Lacy, was serving in the Confederate Army as a staff officer when Union troops arrived and commandeered the estate. His wife and children abandoned the plantation and moved across the river to Fredericksburg.

Built in the mid-1700's, this 1280-acre plantation was an ordinary plantation home that had some extraordinary visitors: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Walt Whitman, Clara Barton and Abraham Lincoln to name a few. It is the only building that both Washington and Lincoln visited.

Once it was taken over by the Union Army, it became a working military post with a strategy center, housing for officers and even was used as a hospital after the battle. Eventually soldiers ripped the paneling off the walls to use as firewood and then marked the walls with graffiti- interesting that the "art" hasn't changed much in over a century!

The top left photo shows the manor's original back entrance which is now the front entrance. Today the National Park Service is housed in the building. The tree in the bottom right photo was there when the battle was fought; most of the other trees on the estate are "new."

By the end of the war, the plantation and manor had been ravaged. Blood stained floors, walls, furniture and draperies. Windows were broken, walls marred and the grounds trampled. It remained a shattered shell of its previous style and elegance until 1920 when new owners restored it to its former beauty.

The proximity to the river (and town) made Chatham Manor a valuable asset to the Union Army. (Chatham Manor is directly behind the camera.) The church spires in Fredericksburg were there at the time of the battle but saw little or no damage.

Back to the battle: The battle was no longer a surprise and General Lee had reinforced his position in two places- directly across the river in the homes that lined the riverfront and in the surrounding hills. When the pontoons finally arrived, Union engineers began putting the bridges together under cover of fog. As the fog lifted, Confederate snipers across the river began picking them off. The Union responded with cannons (causing much damage to the houses across the river) and drove the Rebel soldiers back. The Union Army finally crossed the Rappahannock only to loot the homes and shops, destroying and stealing whatever they could- not their finest moment.

Meanwhile, General Lee was reinforcing his position across town at Marye's Heights, a natural high ground with a sunken road at the base. And as if the high ground and sunken road were not enough of an advantage, there was also a stone fence the entire length of the field.

The Sunken Road is on the other side of the wall, most of which has been restored or rebuilt since the battle. There is one section of original wall at the far right side.

The Union Army advanced from the riverfront, passing houses and businesses, to engage the Confederate Army here at Marye's Heights.

Union soldiers marched up through the now modern neighborhood in the back, which would have been mostly fields and a few houses, past this house that was there during the battle. How close was it to the "front?"

THAT close!

The modest Innis House had wisely been evacuated by the Confederate Army prior to the onslaught of fighting. The National Park Service has restored the outside of the house leaving just one small section to show damage. But the inside of the house is pockmarked from musket and artillery fire. Although the house is locked at this time, you can peer in the windows for a look back into time.

Left- One of only a few original planks in the Innis House showing musket ball damage.

Right- The left gate post of this private family cemetery shows artillery damage.

After a few small skirmishes, the battle at Marye's Heights began in earnest. Union soldiers started advancing across the open fields but division after division was cut down by Confederate artillery and musket fire with no Union soldier getting within 25 yards of the stone wall. Confederate soldiers watched in disbelief as wave after wave (six in all) of Union troops kept on coming straight at the wall but they continued to fight. Mercifully, night came and the fighting stopped. The Union Army suffered nearly 13,000 casualties that day- and the enemy was still in place. The next evening the Union Army began their retreat.

EXTRAORDINARY MEN

As night fell on December 13, 1862 the field in front of the stone wall was littered with dead, dying and wounded Union soldiers. Those that could walk made their way to the back. Doctors and nurses helped those who were near the back, working towards the front. As dawn broke on December 14th, thousands of wounded soldiers were still lying on the field. As the day wore on, their pleas for water, blankets and help were deafening. Both sides were emotionally moved but also fearful to help. Until Richard Rowland Kirkland, a Confederate sergeant filled as many canteens as he could carry with water, gathered blankets and rushed out onto the battlefield... to help his ENEMY! Union soldiers looked on in disbelief while Confederate soldiers stood ready to mow down anyone who even looked like they might harm the sergeant. Kirkland made numerous trips at great risk to himself to help not only people he did not know, but people who just hours before he had been shooting at.

Kirkland was described by friends as a religious, moderately educated, kind young man. He went on to fight in several more battles before being mortally wounded in the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863. His final words were, "Tell my pa, I died right."

Although most of the townspeople fled the battle scene, they often were not far away witnessing the thick smoke in the air and the hoarse screams of wounded soldiers. After the battle, they returned only to find their homes badly damaged, their possessions plundered and make-shift graves in their yards. With perseverance and hard work they set about rebuilding their homes and town.

The soldiers on both sides were mostly young men who were somewhat educated. They were God-fearing, hard working "regular Joe's." Most were passionate about their beliefs and reasons for fighting. Those who died in battle were either buried at the battle site (Union) or returned to Richmond for burial (Confederate). After the war, the bodies of Union soldiers at Fredericksburg were exhumed and reburied at the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

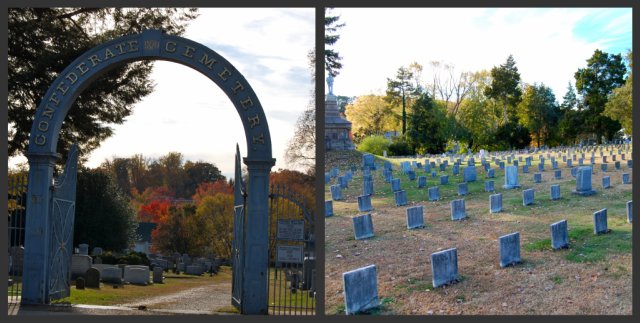

Fredericksburg National Cemetery is the final resting place for more than 15, 000 United States soldiers- most of them Union soldiers who died in the battles around Fredericksburg. Sadly, over 80% of the soldiers are unknown.

The graves seem to stretch as far as we could see. The hill is terraced with row after row of graves. Some have markers with a name and state identified. Other, smaller markers, have two numbers- the top number is the site number and the bottom number indicates how many bodies are buried in that grave.

Mass graves do exist... right here in the United States.

Dead Confederate soldiers that were not moved to Richmond were buried at the Confederate Cemetery in Fredericksburg. It is much smaller and more run-down looking. It seemed that they also used mass graves for unknown soldiers- 2184 of the 3300 Confederate soldiers are unknown.

We wondered if President Lincoln had been alive to oversee the reburial process if there would be just one cemetery for all United States Civil War soldiers, rather than separate ones. As he once said, "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

An interesting historical "What If?" you happened upon!

ReplyDeleteIt was- and I am learning there have been many interesting "what ifs" to ponder in this war.

ReplyDelete